My name is Benjamin von Wong. I’m an artist, I’m an activist, and I create large scale objects of curiosity.

by Benjamin von Wong, Artist and Activist.

The purpose behind my work is to ignite in people a sense of curiosity.

Curiosity is a bedrock of conversation. And when people are curious, that invites us into exploring not just how something happened, but why.

If you want to survive as an artist, you need to make things interesting.

You need to make people want to care about what you do. And I found out that by doing all sorts of weird stunts, I could get people to care about whatever I was up to.

One of the earliest things that I did was tying a model 30 metres underwater in a shipwreck in Bali while I was on vacation with my parents.

And I was like, there’s absolutely no purpose to this, but the stunt captivated people.

So I started doing more and more stunts as much as possible. And along the way started working with different brands.

These projects were really fun. But after a couple years of just attracting attention, I realised that there had to be something more to life than just getting a lot of likes, followers, and filling a wallet up, right?

I started trying to figure out what problems in the world that were really big that could use a little bit of attention.

And there are a lot of problems. In 2016, I discovered the Great Pacific Garbage patch. My mom had found a mermaid tail designer, and I thought, why not?

Why not combine these two worlds? If a mermaid was real, it would be struggling right now.

So we ended up putting a mermaid on 10,000 plastic bottles. And that’s when I realised that even though we’re tackling these really big serious issues, sometimes it’s easier and more palatable to use fiction to tell the truth.

And somehow, it’s more powerful when we’re using fiction to tell the truth. Because if this was an ordinary person, I don’t think it would hit us as hard as seeing a child looking at a beautiful thing we grew up with getting corrupted.

And yet, it’s so beautiful, you need to pay attention to it.

And over time, as I started trying to figure out how to reach more people, I started exploring with the idea of creating more physical pieces, larger pieces.

I didn’t want to just tackle plastics. I wanted to tackle other issues, but it turns out you can’t really escape plastics.

I ended up creating a project for a conference in Cairo. We were trying to capture what it might look like to see how many clothes a single person might use over the course of their lifetime by creating the world’s tallest closet.

As we all know, 75 per cent of textiles is made from plastics, made from fossil fuels.

I tried creating a project around electronic waste. There was a collaboration the largest electronic waste recycler in the world. We wanted to show how we needed to use past technologies to power future devices.

But once again, most electronic waste is actually encased in a ton of plastics.

And so plastics has kind of evolved and grown into this thing that no matter where you look, it exists.

And it’s sort of like the legend of the hydra where you cut one head off and two more spread out, and there’s not really no escaping it, no matter where you look and how you go.

And I think as an artist, one of the things that’s been maybe most frustrating is that regardless of how successful these projects are, regardless of how many people engage, regardless of how many hearts and minds I’m supposedly shifting, when you look at the data, it’s kind of terrifying. This graph shows the amount of plastic produced over the last 50 years.

Global plastics production

There’s this explosion of awareness in plastics, and yet it’s barely made a dent in plastic production.

And the projections of where plastics is going is even more terrifying because we’re expected to triple the amount of plastics produced every single year.

And so if we don’t address plastic production, how do we ever get to the core of the issue itself?

I’m just an ordinary person. I’m not a scientist and a policy person. I’m just an artist. I wandered the world trying to do meaningful things, and you just keep learning about how bad things are.

And it begs the question, well, how can I maybe position myself so that I can create the most effective work possible?

Who are the people that we were trying to really reach at the end of the day?

And so that’s how I ended up in Nairobi, Kenya, where I was working with over 80 ladies to collect over three tons of plastics in the slums of Kibera.

And we happened to be there because there’s this little gathering of important people that was happening.

And I didn’t know if I was going to have permission to build in our installation, but I fundraised for it. We built a team, we came up with a concept, and we somehow managed to get permission at 5:00pm on a Friday night for an installation at 8:00am on Sunday, permission from the United Nations to create a four-storey-tall giant plastic tap spewing plastics all over the environment.

I think for me to be able to create something like this where, when the global plastic resolution was actually signed into place, felt like, okay, maybe now we’re really reaching the people in power.

And I can’t say that, you know, this art installation really changed anything.

I can’t say that the treaty wouldn’t have happened if not for my art, because of all the hard work of everyone else in the room.

But what I thought was so interesting was just seeing how this one thing actually became the common language that everyone could agree upon.

It didn’t matter if you’re a for-profit, non-profit or government organisation.

Everyone could use it and interpret it to talk about something that was important to them.

It’s an important topic, but why are there not more environmental monuments? Why do more environmental monuments not exist when these are such important issues?

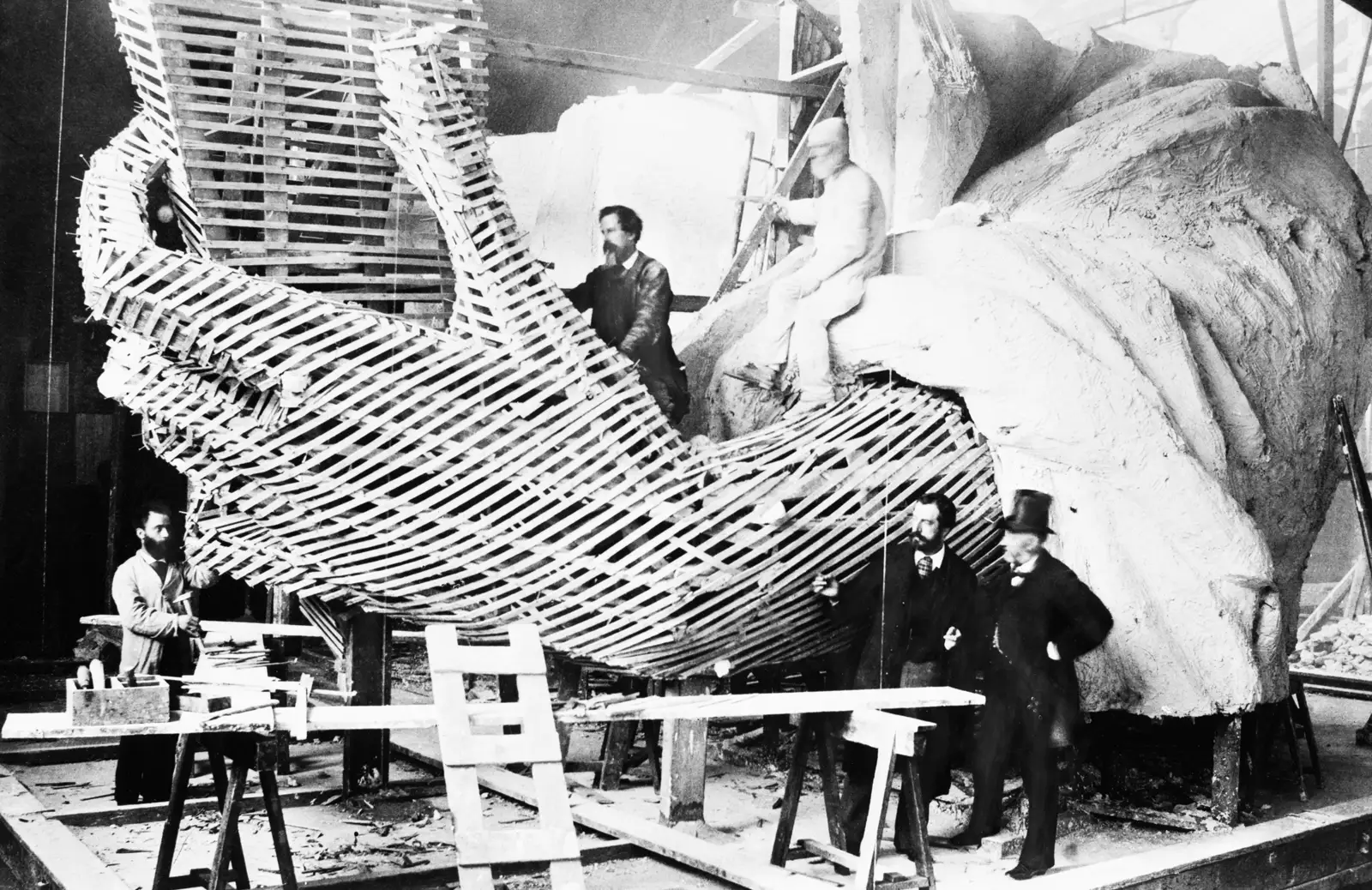

I’m in New York City right now, and when we think of the most famous monuments – we think of maybe the Statue of Liberty. The Statue of Liberty takes this complex idea of freedom and democracy for all, and it’s condensing it into a single sculpture.

Now, anyone can replicate this across the world if they care about freedom and democracy for all.

As times change we might look at it differently start to really remember that, actually freedom and democracy for all doesn’t include people of colour, doesn’t include women.

That’s a problem. So that symbol can now adapt to the times.

Different artists can stand up and adapt it and remix it to talk about something that’s important to them when we fail to live up to those expectations. So it makes the conversation easier for everyone else.

You look at the Statue of Liberty as this amazing thing – and think – I’m sure everyone was asking for it.

But actually, the sculptor Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi spent 23 years fundraising to bring it to life. No one was asking for this. He had to make miniature versions of his statue and sell selfies, collecting 25 cents per photo to slowly raise enough funds to build this thing.

And he didn’t even know how to make it. He only figured out the engineering of the Statue of Liberty three years before it was going to get built.

Most of the time was spent fundraising, and even after he had completed the whole thing and shipped it all the way to the United States, it stayed here in boxes because we hadn’t raised enough money here to create the pedestal for it to stand upon.

And so sometimes we can’t wait for permission to do the things that are really important.

Thinking about the work that I’ve done over the course of my career, what really comes to mind is that I’d never really waited for permission from anyone to do these projects. I wasn’t waiting for a funder to come in to understand, but rather I was just going around looking for a small little group of rebels who believed in the same things that I did.

Whether it was around issues like ocean plastics or fast fashion or electronic waste, these are all issues that really needed a few people to buy into the idea that this is something that truly needed to exist.

And when I think of the plastics issue, which is this big complex issue, there are so many different angles that we can tackle it from, from the science, from the policy, from public action.

And it really is all about figuring out which direction are we trying to go? How do we shift the centre and how are we going to move there together?

We sometimes think that it takes an entire world to agree in order to create change.

But at the end of the day, I think so much of what actually shapes the world is the actions of a small, little powerful group of people that are committed to bringing change.

I wanted to end on this one quote from Margaret Mead, “never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed individuals can change the world. In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.”